While the main party was en route to Shanghai, Mrs. Emaroy J. Smith and her son Mr. Kenneth Smith were in the important city of Foochow, China. The fascinating story of this trip, from the pen of Mrs. Smith, follows:

Now comes the part of our journey that we dislike most embarking in the small vessel Hæan of the China Merchant Line en route to Foochow. We are glad to find aboard Miss Helen Crane, our former fellow-passenger of the Tenyo, who sat next us at table during our voyage across the Pacific. Miss Crane, accompanied by Miss Wells of Shanghai, is going to Foochow to open work for the Y. W. C. A., in response to the awakening caused by the Mott meetings, during which six hundred young women had signed cards expressing their desire to study the Bible and inquire into Christianity. How fortunate they are to have Miss Crane - bright, attractive, versatile, a graduate of Bryn Mawr - respond to that call for service! Could her life be better invested than answering this call from the Orient where she will seek to establish Christian ideals for the girls of China?

English missionaries were driven out of Foochow forty years ago. Less than twenty years ago eleven missionaries laid down their lives as martyrs; now there are 12,000 students in modem colleges.

Miss Crane and Miss Wells, with two young Germans in Chinese mail service, made up our first-class passenger list. We were told there were 150 second-class passengers below us, but only knew this from the fumes of opium that escaped from below. The weather was unfavorable. We were shut in by a dense fog that the captain said was worse than anything he had known for fifteen years on the China coast. Without wireless telegraphy or the modem equipment of the larger vessels to aid us in an emergency, we were relieved when the fog lifted and we were able to make the mouth of the River Min going in with the tide. A party of friends, among whom were Mr. and Mrs. George Hubbard, missionaries of the American Board, Miss Martha Wiley, and Miss Deahl, came out in a launch to meet us.

We were surrounded as soon as our vessel anchored with numberless sampans propelled with long oars by Chinese women. There was great confusion, all of them shouting and struggling for first place next our vessel, in order to secure cargo or passengers. We stepped in one at the risk of our lives. A slender, sinewy Chinese woman, dressed in blue, her black hair coiled in the neck and adorned by a bright flower, stood erect in bow of boat and pushed us away, with her long pole, from the other boats knocking our sides. She then began to use the pole in the water, her strong body swaying back and forth in graceful motion. Her movements reminded us for a moment of the Venetian gondolier, but there the likeness ended. Our boat-woman’s mother was pushing paddle in stem of boat, with grandchildren scrambling about her. On these boats children are born, live, and

die, sometimes four generations living together.

What is this large, stately looking vessel coming alongside us, with large sails wide-spread? On its bow are painted in colors two big eyes. This we are told is a “Ningpo Junk.” Our boat-woman now works swiftly, taking a long pole on the end of which is a hook; she fastens it securely to the side of this passing ship, and thus we are towed to the landing at Foochow City.

Here excitement reigns supreme. There is much shouting and confusion. One wonders how they are to be extricated from it all. We pass from our sampan to another craft and still another before the wharf can be reached. Miss Wiley alights to find coolies and sedan chairs. She shouts loudly in Chinese to keep the party together, and finally we make our way up South Street. We can never forget that memorable ride of nearly four miles in our sedan chairs.

Now we are seeing China. Shanghai was not China. Here is the narrow street, irregularly paved with stones, swarming and seething with Chinese of all classes. Here is the field woman, her hair decorated with silver pins, and large silver rings in her ears. From the ends of a pole carried over her shoulder are suspended heavy buckets. As she passes, you are aware of unpleasant odors and wish you had brought your smelling salts. You discover she is the sewerage channel for conducting refuse from city to field.

Old Chinese women with bound feet are sitting in the doorways; dirty, half-clad children play in the streets. A stream of sedan chairs shouldered by coolies is constantly passing. Sometimes the occupant of these chairs is a Chinese lady belonging to the official class, sometimes a merchant, or it may be a European. The coolies constantly shift the heavy poles from one shoulder to the other. We notice there are deep furrows in their shoulders. There are also deep lines upon their faces that indicate the hard physical toil they are daily subjected to. Their muscles rise in great ridges on limbs and arms, suggesting the strain to which they have been put. As they travel over the rough stone pavement, they shout as they pass to open up the congested street. We pass the fish-market, the open shop where Chinese artisans are working on silver and hammered brass, lacquer, and embroidery.

We were not sorry to arrive at the American Board Compound - we enter a court leading to the house of our lady missionaries. It is bright with flowers, and presents an inviting and attractive picture, in strong contrast to the noise and the motley throng we leave in the busy street. Here we were made most comfortable and very hospitably entertained during our sojourn in Foochow.

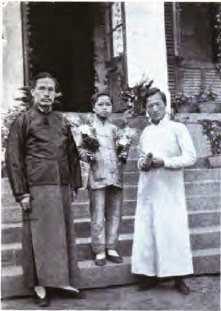

PASTOR HSU CAIK HANG, FOOCHOW

GIRLS AT MR. CHANG’S PARTY, SHANGHAI

UNDER A CHINESE ARBOR, FOOCHOW

CHRISTIAN HERALD ORPHANAGE, FOOCHOW

One day we visited the Christian Herald Orphanage, where we took pictures of the boys working in the garden. The young man who has charge of the garden gave me the following list of vegetables that the boys raised: watercress, red spinach, green peas, long bean, snake gourd, sword bean, com, eggplant, calabash, onion, leeks, pumpkin. Pastor Hang, of Foochow, is at the left of picture, and the boy, holding bouquet of flowers that were later presented to us, we were told, had already shown a very marked tendency for raising flowers and vegetables.

A special program was prepared for us here, the children speaking pieces and singing songs. We were asked to take seats on the platform and to make a speech. We gave them some words of greeting from children of the United States, and told them how American children loved to sing the same songs, study the same Bible, and to work and play as they do.

The day that stands out above all others as affording the purest, richest enjoyment while in Foochow, was the day spent at Sharp Peake. Mr. and Mrs. George Hubbard, Mr. Miner, head of the Methodist Boys’ Academy, Miss Wiley, and Miss Deahl, Kenneth, and myself, with Mr. Ding, an earnest young Chinese, who has charge of industrial work in Foochow, make up our party.

Early in the morning we go aboard our steam launch, which we have chartered for the day, and sail up the beautiful Min River. We pass mountainous islands. From the shore rise towering terraced cliffs, which have been compared to those of the Rhine. The Min compares not only with the picturesque beauty of the Rhine, but has as well the charm gathered from the past of its own traditions. There stands a tower erected by a wife to welcome back her husband from a long voyage, but, when he saw the strange mark, he concluded he had mistaken the estuary, and sailed away never to return. We pass the old arsenal, partly destroyed by the French fleet.

We land at a small fishing village on the shores of Sharp Peake Island. Our coolie carries on his shoulder the huge lunch baskets generously provided by our kind and thoughtful Mrs. Hubbard, who has been unfailing in her attention since our arrival. The people of the village gather curiously about us as we land, but most of them, especially the women and children, ran frightened away when the kodak was pointed toward them, so there was left in our picture only the members of our party, our coolie carrying the lunch baskets, and a few boatmen.

We climb up the hill, the sides of which are planted with young pine trees and terraced with growing crops. Some one has been working here to beautify this hill. On reaching the top we view a group of workmen, starving Manchu soldiers and boys sent up from the city by Miss Emily Hartwell. Now that the Manchu dynasty has been overthrown, their stipend has been withdrawn by the government. Thousands of these men, who have no trades and no means of earning a living, are facing starvation.

BOYS OF INDUSTRIAL SCHOOL, BEACON HILL FARM, FOOCHOW

STARVING MANCHU SOLDIERS AT THE SAME FARM

We find a substantial cottage at the top of the hill. At the entrance is gathered a group of fine Chinese boys, who have led their goats up for our inspection. Miss Hartwell has discovered that Sharp Peake lends itself well to goat raising, that the goats will not only browse over the hills, taking care of themselves, but furnish milk as well. Another boy has brought his ducklings. Boys in China love pets as well as American boys. They love to tend and feed and watch them grow. We are now carried in sedan chairs up Beacon Hill. Here a wonderful view is obtained of both sea and river. We look across the valley - one hill is occupied by a telegraph station, one by Anglican, one by Methodist, and one by Congregational sanitariums. These are resorts where the tired, worn, or sick missionaries may come from the city into this fresh mountain and sea air to recuperate from their arduous labors.

At the top of Beacon Hill are the remains of an ancient landmark, an old stone structure, upon which the beacon fires were lighted, now superseded by the telegraph. At the time of our visit the workmen had been borrowing stone from this structure to work into the foundation of the new Morrison cottage. When our lady missionary discovered this, she was greatly disturbed that one of those historic stones should be displaced. She immediately informed the man in charge that no pay would be forthcoming until all the stones had been carefully replaced. From Beacon Hill we travelled in our chairs up and down the mountainsides to the American Board Sanitarium. This is arranged to afford living accommodations for several families during the summer. It was vacant now and we took possession of one apartment, where we spread the table with the appetizing contents of our bounteous baskets.

One evening we went to the new Manchu Church in the Tartar quarter. We found it filled with men, women, and children expectantly awaiting our arrival. There were special decorations with the word “Welcome” over the platform. Some young men sang the hymn “Blessed be His Name” - having committed it in English for this occasion. The primary children sang several songs accompanied on the organ by their teacher. The young Chinese pastor spoke some ardent words of greeting and welcome, to which we responded. It was a beautiful sight to see the eager, attentive faces of the audience. We were told the people were flocking here since the old restrictions have been removed which segregated them. They were formerly allowed no association with Chinese or foreigners. After the meeting the young men had provided cakes and sweetmeats for us, which were arranged on a small table decorated with candlesticks, flowers, etc.

We visited the East Gate Industrial School, where we found Mr. Ding Bing Yeng in charge. We went into a small room adjoining his office, where on a bed in the comer lay the old woman who had picked him up as a waif and adopted him when a lad. She was a pitiful looking object, with sightless eyes, and lay here day after day praying to die. We were told that often at night Mr. Ding was kept awake by the upbraiding of this sick, repulsive looking old lady. She often complained of his abusing her, but he ministered to her tenderly and patiently, expressing a very beautiful Christian spirit.

We saw the women, men, and boys busily working at their looms weaving cloth, braid, rugs, etc. Here were rescued girls who had been sold as slaves by husbands and fathers. One young girl sat spinning with a baby in her lap. Her husband had sold her to the Hunan soldiers. She had cut off her hair, believing they would not want her if she was thus disfigured.

In the afternoon we went to the Hartwell Memorial Church, where there were gathered about 350 Bible women and day school pupils. There was an address by the pastor; the children sang songs; two earnest talks were given by Chinese women, to which I was invited to respond. After the meeting we went in to see the girls’ day school and partake of refreshments that had been provided.

A dinner was given in our honor that evening. Mr. Beard, president of Foochow College, with some of his teachers and students, was present. This was a real Chinese feast. The dishes consisted of a great variety of courses, among which were clams, mussels, snails, shark’s fins (a rare and expensive delicacy), pigeons’ eggs, meat dumplings, stewed biba, orange soup, the latter served last, and many other delectable dishes too numerous to mention.

Having long known of Dr. Kinnear’s work, we were glad of the opportunity of visiting his new hospital. We saw him treating the eyes of a procession of poor Chinese men. One man lay on a cot with bandaged eyes, having just gone through an operation for the removal of cataracts, a practical demonstration of the restoration of sight to the blind. We saw a young man with a shoulder cut open, the doctor having just removed a dead bone. It was hard to believe this fine building could have been built for $8,000.

One day we were entertained by Mrs. Sites for tiffin, Mr. Sites showing us through the fine buildings of the Methodist College. An English lady, Miss Crump, was also a guest, and later showed us her lace industry, a very unique work she has developed, teaching many of the wives of coolies lacework, and at the same time to read and study the Bible. She has in connection with this a room fitted up as a chapel where religious services are held every Sunday morning.

We enjoyed a call upon Miss Garretson, principal of the Girls’ School at Ponasang. This school has a fine, intelligent body of students. We were shown through the girls’ dormitories, and then taken to the roof of the building, where a far-reaching view is obtained of the surrounding landscape. One observes how the high places about the city have been occupied by Christian work. We look in one direction and see the Methodist School building rising from Nantai Island; in the opposite direction rises Foochow College, marked by the White Pagoda. We know that from these colleges will come forth men and women who will be the future leaders of China. They will receive in these Christian institutions of learning ideals and visions which will help them to uplift the oppressed of their own people.

(Taken from Frank L. Brown’s Sunday School Tour of the Orient, published in 1914, written by Mrs. Emaroy J. Smith.)