Fuhchau, as the name of the city is known among foreigners, being according to the Mandarin pronunciation; Hok-chiu, as known to its inhabitants, according to the local pronunciation - the “Happy Region” - is the capital of the province of Fuh-kien. It is situated about thirty-five miles from the month of the River Min, and two and a half miles from its northern bank, in a valley fifteen miles in diameter from north to south. Its longitude is 119°20′East, and latitude 260°05′North, a little farther south than the most southern point of Florida. Of the five ports opened to foreign trade and residence at the close of the Opium War, by treaties made in 1842-’44 between China and England, France, and the United States, Fuhchau occupies the central position, being situated between Amoy on the south and Ningpo on the north, and about equally distant from Canton and Shanghai.

Fuhchau is a walled city, having seven massive gates, which are shut at nightfall and opened at daybreak. Over each of the gates are high towers, overlooking and commanding the approach to them. At intervals on the walls are built small guard-houses. The walls are from twenty to twenty-five feet high, and from twelve to twenty feet wide, composed of earth and stones. The inner and outer surfaces are faced with stone or brick, and the top is paved with granite flag-stones. The circuit of the walls is about seven miles, and can be traversed on the top on foot, or in sedan-chairs, a1fording a variety of novel and interesting views in quick succession. Outside of each gate are suburbs. The southern suburb, known to the Chinese under the general name of Nantai, extends southward toward Amoy nearly four miles. Outside of the east, west, and southwestern gates there are also extensive suburbs. The suburbs outside of the three most northern gates, two of which lie on the eastern side of the city, are far less extensive and important than the other four.

The population of the city and suburbs bas never been accurately, and therefore satisfactorily ascertained. The inhabitants of the seven suburbs are believed to be as numerous as the inhabitants of the city itself. The population of both has been estimated by residents and visitors at all figures, from 600,000 to 1,250,000. Including the people dwelling in boats, who are quite numerous, it probably would not be far out of the way to say that the population amounts to 1,000,000. A few years ago it was reported at Fuhchau that a certain mandarin had informed the English consul that the people within the city walls numbered 500,000.

Like Canton, Fuhchau is a city of the first rank, being not only the capital of Fuh-kien province and the residence of its governor, but also the official and actual residence of a viceroy, or governor general, whose jurisdiction extends over Fuh-kien and Chekiang, its adjacent northern province. The word fu, sometimes affixed to its name, as Fuhchau-fu, indicates that it is the chief city of a prefecture or department, and, so considered, it has the same rank as Ningpo. It is also the residence of two district magistrates, the boundary-line of whose districts passes through the city from north to south. Besides, it is the residence of a large number of civil and military officers of high grade. Among them are the Tartar general, who is of the same rank as the viceroy, the provincial criminal judge, the provincial treasurer, the commissioners of the salt and the provision departments for the whole province, and the literary chancellor. It is the political, literary, and commercial centre of a province, whose area is over 68,000 square miles, and whose population, according to the census taken in 1812, was then more than 14,600,000. A census taken in 1842 makes its population over 26,000,000. There are always at this city a large number of expectants of office of high grade awaiting their actual appointments. Numerous gentry reside here, who have retired from office in other parts of the empire.

It is a great literary centre, not limply because it is the official residence of the imperial commissioner, the literary chancellor, but because there are many men living here of high literary attainments in a Chinese sense, and also because all of the literary graduates of the first degree over the province of Fub-kien, which includes the large island of Formosa, must appear at Fuhchau twice every five years to compete in the provincial examination hall for the second degree, if they desire to compete for that degree at all. Usually six or eight thousand of the educated talent of the whole province assemble here on these interesting and exciting occasions.

Legitimate foreign trade at Fuhchau was insignificant until 1853. The opium trade had been extensively carried on for several years previous to that period by means of receiving ships stationed near the mouth of the Min. In 1853, Fuhchau came suddenly into importance as a market for black teas, mainly through the enterprise of Messrs Russell & Co., an American firm. Previous to this year no teas were shipped directly from this port to any foreign country. In the spring of that year the American firm mentioned sent from Shanghai their Chinese agents into the tea districts lying near the western and northwestern borders of this province, and bought up large quantities of tea, and had it transported in small boats down the River Min to this city. By the time it was ready for shipment foreign vessels arrived, according to agreement, and took the tea direct to foreign countries. In that year fourteen foreign vessels arrived at Fuhchau, and in 1858 one hundred and forty-eight vessels.

A few statistics will show the rapid growth of the tea trade at this place. The exports of tea to foreign countries in the year 1856-’57, from April 30th, from Canton, was 21,359,885 lbs.; from Shanghai, 36,919,064 lbs.; and from Fuhchau, 34,019,000 lbs.; and that only three years after the trade was commenced at the latter port. During the tea season, beginning with July, 1859, the exports of tea from Canton to the Unite States amounted to 3,558,424 lbs.; from Amoy, 5,265,100 lbs.; from Shanghai, 6,893,900 lbs.; and from Fuhchau, 11,293.600 lbs.; the quantity sent from Fuhchau being nearly one million pounds more than the combined amount sent from Canton and Shanghai. During the same period Canton sent to Great Britain 41,586,000 lbs.; Shanghai sent 12,331,000 lbs.; Fuhchau sent 36,085,000 lbs., or about two thirds as much as both Shanghai and Canton. In the tea season, 1863-’64, ending with May 31st, Fuhchau sent to Great Britain 43,500,000 lbs.; to Australia, 8,300,000 lbs.; and to the United States, 7,000,000 lbs.; in all amounting to more than fifty-eight millions of pounds. From these data the relative commercial importance of Fuhchau is easily seen. It has become by rapid strides one of the most important of the consular ports in China for the purchase of black teas. It was currently reported in 1850-’51 that the English government seriously contemplated giving it up, or at least exchanging it for some other port whenever an opportunity should occur, because it had no commercial importance.

In exchange for its tea, which is the principal export from Fuhchau, to foreign countries, it receives opium, cotton and woolen goods, si1ver, and a few unimportant articles. In the year ending December 31st, 1863, the imports into Fuhchau from foreign lands amounted to over ten and a half millions of dollars. Of this sum, the value of the opium imported was over five millions. Unlike Shanghai and Canton, it furnishes no silk for exportation.

It has a large trade with other ports on the sea-coast by means of native craft, as well as in foreign vessels, giving and receiving some of the other luxuries and the necessaries of life. Frequently rice is imported in large quantities from Formosa and from Siam. An immense amount of timber and paper is brought down the Min from the upper or western portions of the province, and taken to various ports north and south. It annually exports large quantities of dried and preserved fruits. Twelve and fifteen years ago, not unfrequently there were several hundred Chinese junks in the harbor at the same time, discharging and receiving cargo. Of late years, many Chinese merchants charter foreign ships to carry away and bring back produce and merchandise, on account of their increased speed and safety compared with Chinese crafts. Native junks almost always come up the river and anchor opposite the city.

While the high native officials, civil and military, live within the city, the foreign consuls, vice- consuls, and interpreters reside two and a half miles outside the city, on the hill near the south bank of the Min. No foreign merchant lives in the city, nor is there any foreign hong or store inside the walls. The principal native wholesale merchants do their business in the immense suburbs surrounding the Great Temple Hill. The principal native banks are also in the southern suburbs.

A part of the eastern and southern sections of the city is devoted, though not exclusively, to the residence of Manchu Tartars. They are subject, not to Chinese, but to Tartar officers. There is no wall dividing them from the Chinese, as has been sometimes represented. A few Chinese live scattered about in the sections originally given op to the Tartar population. The Manchus number at present probably between ten and fifteen thousand. All of the males professedly belong to the army, though the number of those who actually receive pay in money, and rations in rice monthly, as soldiers, is said to be limited to one thousand. When any of their number dies, another Tartar takes his place on the roll of soldiers, and succeeds to his salary and perquisites. These soldiers are not called away from Fuhchau to serve in the army, but remain at home, assisting when called upon to guard and keep the city. They spend their time principally in the practice of archery, horsemanship, and shooting at a mark with matchlock guns. Until late years none of them engaged in any business for the sake of gain. But poverty has driven a few to open shops, where some of the commonest articles are offered for sale. They generally speak among themselves the Mandarin or court dialect, though some understand the Manchu language. Most or all are able to speak the colloquial dialect. They are not noted for their knowledge of Chinese literature. Within a few years, more have applied themselves to the study of Chinese books than formerly. As a class, they are indolent, ignorant, and proud.

They have the reputation of being overbearing and insolent toward the Chinese – a natural and almost inevitable consequence of their relative positions. They are the masters and the lords; the Chinese are subjects. The Manchu and the Chinese men shave their heads and braid their cues alike; the former having obliged the latter nearly two hundred years ago to adopt the Manchurian national costume of dressing their hair. The Manchu ladies do not compress their feet as do the upper class of Chinese ladies at this place, and in this respect compare favorably with them. They are of a large frame, more noble in appearance, and more independent in action, than are the Chinese females. The same remark is true of the Manchu men compared with the Chinese men. The two races are not allowed to intermarry.

The Tartars here are descendants of a colony of Tartars who came from Peking by the will of the emperor in the early part of the present dynasty. They regard themselves as distantly related to the imperial family, and all owe their support to the favor of the government. They may be always relied upon by the Peking government as faithful to it under all circumstances. In the result of a successful rebellion against the government, in case they should not be able to make their escape to the land of their forefathers, an extremely doubtful event, they would all lose not only their salaries and their property, but also their heads; for no successful rebel emperor would allow any of the Tartars to live in the country.

Foreign vessel of large tonnage anchor about ten miles below the city of Fuhchau, at Pagoda Anchorage, so called on account of a pagoda built on a hill on an island in the vicinity. Above that anchorage the water is too shallow for large vessels to endeavor to proceed with safety. Here the mail steamers, which arrive usually at least once in two weeks, come to anchor, sending the mails up to town in a small but well-manned boat. Not unfrequently are there twenty-five or thirty sailing vessels and steamers of several different nationalities to be found at Pagoda Anchorage, discharging and receiving their cargoes, where thirteen years ago there was not one foreign vessel. The vessels lie in the middle of the Min, and their cargoes are transferred into lighters, which ply between the town and the anchorage.

The entrance to the river is marked by bold peaks and high land – unlike the entrance to the Yang-tse-Kiang, en route to Shanghai from the China Sea, or the entrance of the White River at Taku, en route to Tientsin and Peking from the Gulf of Pechele. Foreign pilots usually take the charge of vessels until they have fairly entered the river, when they yield to native pilots, who navigate them until they reach Pagoda Anchorage. The banks of the Min are lined by lofty hills, generally destitute of thrifty trees. Many of the hills are terraced and cultivated to their tops, presenting in the spring and summer an interesting and unique appearance. The foreign visitor never fails to admire the charming and romantic scenery lying between the mouth of the Min and the anchorage. It has been thought by some European travelers to resemble the scenery of Switzerland in its picturesqueness and grandeur. Americans are more frequently reminded by it of the Highlands of the Hudson.

The Min having separated into two parts six or eight miles above Fuhchau, the branches unite not far above the anchorage, and their waters tow together into the ocean. The city of Fuhchau lies to the north of the northern branch. The southern branch passes nearly parallel with the northern, the two forming a narrow and fertile island, fifteen or sixteen miles in length, and three or four miles in width in its broadest part.

Following up the northern branch of the river from the Pagoda Anchorage, about half way to Fuhchau, on the right hand, is the mountain called Kushan, or Drum Mountain. Its peak is about half a mile high. A large and celebrated Buddhist monastery is situated half way op the mountain, a favorite place of resort with some foreigners and Chinese in the hot summer months. The temperature at the monastery is sometimes eight or ten degrees lower than in the city in the valley below. The monastery takes its name, the “Bubbling Fountain,” from a spring of clear cold water in its vicinity. Several score of Buddhist priests are usually found at the monastery, where they spend their time in studying the rituals of their order, and in the performance of the regular religious l rites and ceremonies. The landscape of the valley of the Min, viewed on a clear summer’s day from the top of the mountain or from its side, is very fine, consisting of numerous small streams and canals funning in all directions, several scores of hamlets dotting the country, and rice-fields in a high state of cultivation. These, once seen, are not soon forgotten.

Soon after passing Kushan, proceeding up the river, two lofty pagodas become visible, three or four miles distant, situated on the right hand, and inside the city, near the southern gate. A lofty watch-tower marks the extreme northern angle of the city. The foreign bongs and the flag-staffs of the English, American, and other consuls, gradually become more and more distinct, lying principally on the left band, on the southern bank of the Min. The hongs and residences of foreign merchants, missionaries, and officials, being built in foreign style, afford a pleasing and striking contrast to the shops and houses of the Chinese. From some parts of the river opposite the city, the brick chapel belonging to the Methodist Mission, and the stone church where a chaplain of the Church of England officiates, both located on the hill near the southem bank of the river, can be readily recognized by their belfries.

In the Min, abreast of the city, is a small, densely-populated island, caned Chung Chau by foreign merchants, and Tong Chiu by the natives, i.e., “Middle Island.” It is connected with the northern bank of the river by the celebrated “Bridge of 10,000 Ages,” or the Big Bridge. This bridge is reported to have been built eight hundred years ago, and is about one quarter of a mile long, and thirteen or fourteen feet wide. It has nearly forty solid buttresses, situated at unequal distances from each other, shaped like a wedge at the upper and lower ends, and built of hewn granite. Immense stones, some of them nearly three feet square, and forty-five feet long, extend from buttress to buttress, acting as sleepers. Above these stone sleepers a granite platform is made. On the sides of the bridge are strong stone railings, the stone rails being morticed into large stone pillars or posts. Until eight or nine years ago the top of the bridge was partly taken up with shops. Now the whole of the bridge is devoted to the use of passengers, and the conveyance of merchandise to and fro. The bridge connecting Middle Island with the south bank of the river, called the “Bridge in front of the (salt) Granaries,” is built in a similar manner, but is only about one fourth as long as the Big Bridge. Lighters and other boats which have movable masts pass under the Big Bridge, but the junks from Ningpo, Amoy, and other places, which come up the river, anchor below these bridges and Middle Island. There are no ferry-boats which ply regularly between the north and south banks of the Min, though there are numerous boats which can be hired for a few cents whenever necessary to cross the river above and below the bridges. From early dawn until nightfall these bridges are usually thronged by travelers on foot or in sedans, and by coolies carrying produce and merchandise back and forth.

To the northwest, and distant six or seven miles across the Min, is another celebrated tone bridge, called sometimes the “Bridge of the Cloudy Hills.” That and the Big Bridge are built, in a similar manner. The scenery in its vicinity is mountainous and interesting.

The foreign residents live principally on the hill near the southern bank of the Min. Standing on that hill, and looking toward the east, north, and west, the scenery is beautiful. To the eastward, looming up five or six miles distant, is “Drum Mountain.” Nearer is the river, with its multitude of junks and boats. As one glances in a more northern direction, parts of the city come within range. In it the white pagoda and the watch-tower are prominent objects. Between the city and the river, apparently about midway, may be seen the roof and belfry of a brick church belonging to the Mission of the American Board. In the city Black Rock Hill is conspicuous, and nearer, in the suburbs, are seen Great Temple Hill and several spacious foreign hongs. To the northwest and the west the numerous boats on the river and the distant hills present a diversified and striking appearance.

From the top of the Great Temple Hill, looking toward the south, the prospect is also fine. Probably there is not a better stand-point in the suburbs than that hill for taking a view of the most prominent objects to be seen in the valley of the Min. The river, spread out to the west, south, and east, covered with its countless boats, the bridges on each side of Middle Island, with their passing throng, foreign hongs, the British consulate, flag-staffs and tags of various nationalities, etc., always interest the beholder. In the distance to the southward, the hills called the Five Tigers, and other ranges, add variety and picturesqueness to the scenery. To the east and to the west are highly-cultivated plains, villages, canals, etc. On the north the city is seen much more distinctly than from the hill on the southern bank of the river.

Fuhchau contains within its walls three principal hills, two in its southern and one in its northern quarter. On account of these hills it is sometimes called in writing and in books the Three Hills. It is also frequently styled the City of Banian, or the Banian City, on account of the great number of mock banian-trees which are growing every where in the city and vicinity. The branches of this species of banian seldom extend to the ground and take root, like the Indian banian, though they sometimes thus take root. The pendent branches look so much like whiskers that the common name for them among the Chinese is the whiskers of the banian. They hang down several feet from the main horizontal branches, and swing back and forth in the breeze. A single tree with its outstretched branches sometimes shades a space of ground from one hundred to one hundred and fifty, feet in diameter.

The streets of the suburbs and the city are narrow and filthy. They oftentimes are not as wide as a medium-sized side-walk in cities in Western lands. Some of the principal streets in places are so narrow that two sedans can not pass each other. One must seek a wide spot and stop while the other passes along. Shop-keepers are in the practice of taking up part of the street in front of their establishments with their movable sign-boards, which are over a foot wide, placed in perpendicular position, making the street actually allotted to the public so much the narrower. The eaves of the stores and native hongs are so arranged that, in case of rain, the water falls down into the middle of the street. There are no eave-troughs in use. It is impossible in a hard shower for one to pass through the streets, even with an umbrella, and escape a thorough wetting.

There are no glass windows in the fronts or sides of shops and stores in Fuhchau. The front part of stores, etc., is constructed of upright movable boards fitted into grooves in two pieces of timber, one fastened on or near the door-sill, and one put at the top of the front of the room. These boards are numbered, and may be taken down and put up again expeditiously. At night they are slipped into the grooves, and fastened securely on the inside. In the morning they are taken down, letting the passer-by see all that is transacted in the store, and furnishing all the light that is needed. In storms the wind oftentimes blows the rain into the establishment; in cold weather the clerks and customers are exposed to chilling draughts of wind. Usually the whole front sides of the shops, facing the street, except a passage-way to the back, is occupied by a counter about four feet high.

The streets are paved with granite tag-stones. In case of a hill occurring in the street, it is ascended and descended by means of a tight of stone steps. On this account, even if the streets were wide enough, no wheeled vehicle could be used in them. Merchandise, furniture, etc., are carried to and fro through the streets by coolies. If the load is about a hundred pounds’ weight, or less, and can be divided into two equal parts, not too bulky, each part is slung by means of ropes on the ends of a carrying-pole, four or five feet long, which is placed across the shoulder of the coolie. It is thus carried to its destination, one part coming before and the other part coming behind the bearer. It can not be carried crosswise or at right angles to the street, for that coarse would prevent oftentimes any one passing from an opposite direction; it would generally occupy nearly all the street. Bulky and heavy articles, too bulky and too heavy to be thus carried by one man, are slung upon the centre of a strong carrying-pole, six or more feet in length. The ends of the pole are placed upon the shoulders of two or more men, and the load carried between them. Sometimes eight, or sixteen, or a greater number of persons are required to carry heavy articles in this manner. Occasionally a load is carried on the shoulder or the back, steadied by the hands of its bearer.

The roads in the country are narrow, and not adapted to traveling or transporting merchandise in carts or wagons. Oftentimes they are paved with granite, and only wide enough for two to walk abreast with ease and safety. Every five or ten Ii, on the most traveled roads, there are rest-houses, where the tired traveler or coolie may stop and refresh himself. There are no toll-gates in this section of the empire.

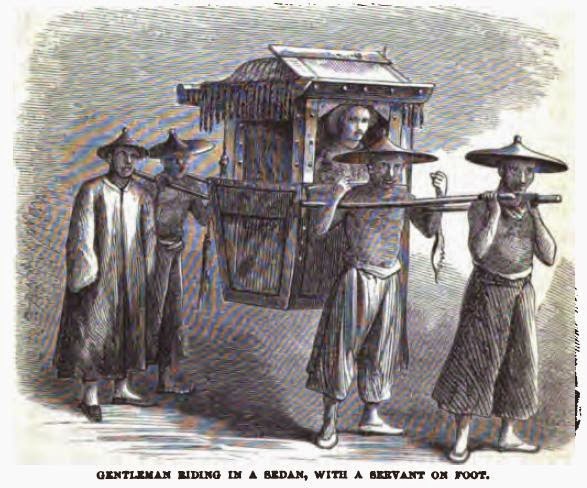

Traveling on land is performed on foot or by sedan-chairs, carried, in the case of a civilian, by two or three men. Officers of a certain grade may have four bearers. Those of the highest rank may have eight bearers. Military officers of a low rank, and a class of interpreters or assistants of high civil mandarins, sometimes ride through the streets on ponies, but the common people never ride on horseback. In case a horse is rode through the crowded streets, a boy or the groom precedes, crying out “Horse!” “horse !” and clears the way, else various accidents would often occur.

The hills in the vicinity of the city and suburbs of Fuhchau are devoted principally to burying the dead, the valleys and the level land to the residences of the living. While foreigners prefer to reside in elevated and airy positions, as on the sides or the summits of hills, the Chinese reserve these situations for the sepulchres of their honored dead. The graves of the poor Chinese are made much at random on the hills, on spots where they succeed in securing the privilege of digging them; while the sites for the graves of the wealthy are determined by the nice rules of the art of Geomancy, à la Chinois, having especial reference to the future good fortunes of the families of the living. No dead body may be buried inside the city, nor may a corpse be carried into any of the gates of the city. It may not enter the city on any consideration, no matter how high the rank of the deceased, or how influential and respected his family. The most fashionable form for a grave and its surroundings, considered as a whole, is what by foreigners is usually called the horse-shoe pattern, from its general resemblance to a horse-shoe. It is also called sometimes the Omega grave, from its resemblance to the Greek letter Omega. The rich spend a large sum of money in erecting the grave-stones, and in embellishing the sides and the front of the grave. In the case of high officers, there are often large granite images of a pair of horses, sheep, and other animals, arranged some distance in front of the spot on which the corpse is buried. One of each kind of animal is placed on the right and left hand sides, corresponding to each other. Occasionally there are two granite images or statues of men, arranged in like manner. These granite images, some of which are larger than life, seem to take the place of pillars and monuments, so common at the West, in connection with the tombs of the distinguished dead.

The first Protestant Mission at Fuhchau was established by a missionary of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions in January, 1847. The Mission has averaged three or four families since its commencement. In April, 1856, occurred the first baptism of a Chinaman at this city in connection with Protestant Missions. In May, 1857, a brick church, called the “Church of the Savior,” built on the main street in the southern suburbs, and about one mile from the Big Bridge, was dedicated to the worship of God. Its first native church, consisting of four members, was organized in October of the same year. In May, 1863, a church of seven members was formed at Chang-loh, distant seventeen miles from the city. In June of the same year a church of nine members was organized in the city of Fuhchau, having been dismissed from the church in the suburbs to form the church in the city. For the first ten years of this Mission’s existence only one was baptized. During the next five years twenty-two members were received into the first church formed. During the next two years twenty-three persons were baptized. Between 1853 and 1858 a small boarding-school, i.e., a school where the pupils were boarded, clothed, and educated at the expense of the Mission, was sustained in this Mission. Among the pupils were four or five young men, who are now employed as native helpers, and three girls, all of whom became church members, and two of whom are wives of two of the native helpers. There are at present a training-school for native helpers, and a small boarding-school for boys, and a small boarding-school for girls connected with the Mission. It employs six or seven native helpers, and three or four country stations are occupied by it. Part of the members of this Mission live at Ponasang, not far from the Church of the Savior, and part live in the city, on a hill not far from the White Pagoda, in houses built and owned by the American Board.

The Mission of the Methodist Episcopal Church was established in the fall of 1847. It has had an average number of four or five families. In 1857 it baptized the first convert in connection with its labors. In August, 1856, a brick church, called the “Church of the True God,” the first substantial church building erected at Fuhchau by Protestant Missions, was dedicated to the worship of God. It is located near Tating, on the main street, in the southern suburbs, about two thirds the way between the Big Bridge and the city. In the winter of the same year another brick church, located on the hill in the suburbs on the south bank of the Min, was finished and dedicated, called the “Church of Heavenly Rest.” In the fall of 1864 this Mission erected a commodious brick church on East Street, in the city. Its members reside principally on the hill on which the Church of Heavenly Rest is built. One family lives at a country station ten or twelve miles from Fuhchau. This Mission has received great and signal encouragement in several country villages and farming districts, as well as in the city and suburbs. It has some eight or ten country stations, which are more or less regularly visited by the foreign missionaries, and where native helpers are appointed to preach regularly. It has a flourishing boys’ boarding-school, and a flourishing girls’ boarding-school, and printing-press. At the close of 1863 there were twenty-six probationary members of its native churches, and ninety-nine in full communion. It employs ten or twelve native helpers. It has established a system of regular quarterly meetings and an annual conference in conformity with the discipline of the Methodist Episcopal Church.

The English Church Missionary Society established a Mission at Fuhchau in the spring of 1850. It has met with many reverses, and has not averaged two families. Its members have always resided within the city on Black Rock Hill. It has two large chapels, located on South and on Back Streets, two of the most important streets in the city. It employs two or three native helpers, and has ten or fifteen baptized Chinese under its care and instruction. Many of the small chapels, and some of the large church buildings, in connection with these three Missions, whether in the city, or in the suburbs, or at the country stations, are opened daily for preaching in Chinese. All who please to come in are welcomed.

All these Missions have in former years distributed, in large numbers, tracts and parts of the Scriptures prepared in the general language of the country. A considerable number, prepared in the local dialect, have also been published. The Methodist Mission in 1864 completed the translation and publication of the New Testament in the local dialect.

In some years, at the regular literary examinations of candidates for the first and for the second degree at Fuhchau, the opportunity has been embraced to distribute large numbers of volumes and tracts among the competitors – e.g., in 1859, about nine thousand graduates of the first degree, from all parts of the province, including the island of Formosa, assembled at this place to compete for the second degree. The English and some of the American missionaries availed themselves of the occasion to distribute to the competitors about seven thousand tracts and volumes, besides two thousand copies of portions of the Bible. The plan was to stand near the outside door, and give to the candidates as they came out of the places where the examinations had been held. Most of the volumes were distributed at the residence of the literary chancellor at the close of the supplementary examinations of some of the candidates preparatory to competition for the second degree. The rest were given away to them as they came out of the Provincial Examination Hall at the termination of their last general examination before the imperial commissioners. Only a few out of this immense crowd refused to accept the books; the vast majority seemed glad to obtain them.

In 1850, two missionaries, sent by the Swedish Missionary Society, arrived at this place, intending to establish a Mission; but the untimely death of one, the result of an attack by pirates on the Min, near Kinpai Pass, in the fall of the same year, frustrated the enterprise. In 1852 his associate left China for his native land.

There is a small community of native Mohammedans at Fuhchau. In the western and northwestern parts of the empire they are very numerous and powerful. The resident priest, who lives on the premises on which the mosque is built, is reported to come from the western portion of China. These premises are on the west side of the main street in the city, running north and south, not far from the South Gate. On tablets put over the principal door and posts of the mosque are gilt inscriptions in Arabic. The Calendar, or list of days when fasts are observed or worship is performed, usually contain a few sentences in Chinese, which speak of several worthies mentioned in the Old Testament. Very little is known by the common people about the Mohammedans and their worship or creed. The Mohammedans are exceedingly uncommunicative of subjects relating to themselves.

Near the South Gate, outside the city, is a Roman Catholic church, built, according to report, since the treaties opening this port to foreign residence and tolerating Romanism in China were formed. The number of native converts to Romanism living in the city and suburbs is not known, but it has been vaguely estimated at several thousand. Some of the boat population are Roman Catholics. Masses are said regularly every morning and evening during the week; occasionally other religious services are held on week days. Worship is also conducted statedly on the Sabbath. The Sabbath is not observed as a day of rest from labor, and there is nothing in the general conduct of the Chinese Catholics which distinguishes them from the pagans among whom they live. They do not worship the ancestral tablets in their houses.

Usually one or more European priests reside on the premises connected with the church. They dress in Chinese costume, shaving the bead and braiding the cue. The priests and the Chinese Catholics shun the acquaintance of Protestant missionaries and converts connected with Protestant Missions, and are very wary and silent in regard to matters which concern the Roman Catholic Mission. A boarding-school for boys is sustained on the Mission premises. Some or all of the pupils are trained thoroughly in the doctrines and practices of the Roman Church preparatory to entering on the functions of the Roman priesthood. Near the church is a new and convenient building, erected expressly, a few years ago, for the purpose of saving alive and bringing up the little girls found deserted by their parents, or who should be brought there by them. There is a very appropriate inscription, in large Chinese characters, over the front door of this asylum, saying, “When thy father and thy mother forsake thee, the Lord will take thee up.” This institution is under the oversight of several nuns, or sisters of Mercy, from Manilla. It is reported as being in a flourishing state.

The church is well built. It has an inscription in large gilt characters upon its front, implying that it is erected in accordance with the especial permission of the emperor. Upon its roof is a large cross, which may be seen from a considerable distance. No seats are provided in the church for the worshipers, but mats on which they kneel. The men use one side of the church and women the other. Near the pulpit or altar is an image or picture of Mary, and an image of the Savior on the Cross, and on the walls are numerous pictures of Romish saints. A tablet to the emperor, having upon it the usual inscription which is applied only to him, several years ago was to be seen near the altar, in such a position that when the worshipers bowed toward the altar, and the images and pictures near it, they necessarily also bowed toward the tablet.

The Roman Catholic priests here operate secretly. Perhaps they labor principally among the descendants of Roman Catholics of former generations. During about two hundred years there have been native Romanists at this place. Sometimes they have been severely persecuted by the government, and some have remained faithful to their professions through all their trials, and have brought up their children in the Romish faith.

The doors of the church are not open to all Chinese who desire to attend the worship, as all the Protestant missionaries open the doors of their chapels and churches to the public. Only members of the Romish community, or those who are properly introduced, are permitted to enter the church and remain during service. The foreign priests or their native assistants hold no public preaching service where their doctrines are explained and enforced. Here, as elsewhere, Romanism is evasive, and screens itself from observation, working in the dark and secretly. Protestantism boldly and openly solicits examination. Romish missionaries to the Chinese shut the door against all except the initiated and the well-disposed. Protestant missionaries throw open the churches and chapels to all, whether friendly, inimical, or indifferent, whether strangers or acquaintances.

The Romanists do not distribute the Bible, or even religious tracts, to the public nowadays. It is doubtful whether they have made into Chinese a complete translation of the Bible for the study of the native priests or for their own use. They have a large variety of tracts and books, which may be obtained by proper persons by applying at the proper quarters. Some of them were prepared over two hundred years ago by converts in high stations at court. The Catechisms and books used in schools by their catechumens and converts are intensely characteristic – e.g., in a certain Catechism, the second commandment is expunged from the Decalogue, in accordance with the practice in Western lands, and, to make up the requisite number, the tenth is divided into two.

Only one public distribution of Roman Catholic books is known as having occurred at this place between 1850 and 1863. Among the books which were given away on that occasion was one which had a singular stamp or imprint of six Chinese characters in red ink. These characters, taken in connection with other characters in red ink also stamped upon the book, informed the reader that the religion of the Lord of Heaven was different from the religion of the kingdom of the Flowery Flag. It is necessary to explain that the distinctive name in China for the Roman Catholic religion is the “religion of the Lord of Heaven,” while the common name for the United States of America is the “kingdom of the Flowery Flag,” a term derived doubtless from the unique appearance of the stars and stripes of the national flag. The meaning intended to be conveyed by the imprints was that Romanism was different from Protestantism. It would seem that the Romanists had been aroused, by the zeal of Protestant missionaries in distributing books, to an unwonted exhibition of zeal in the distribution of Roman Catholic books. But, in order to protest against Protestantism, and not knowing any better name to give it than the name denoting the nationality of the greatest number of Protestant missionaries at Fuhchau, they caused some or all of the books given away on the occasion referred to, to be stamped in a prominent place and in a color which would attract attention, with a sentence meaning that the religion of Heaven’s Lord was not the same as the American religion!

There are many points of similarity between Roman Catholicism and Chinese Buddhism. The common people here do not discover many points of dissimilarity between the lives of the converts to Romanism and the native adherents of Buddhism. The prominent points of similarity are the vow of celibacy, monastic seclusion, monastic habit, holy water, counting beads, fasting, forbidden meats, masses for the dead, worship of relics, canonization of saints, use of incense and candles, bell and book, purgatory – from which prayers and ceremonies deliver – use of a dead language, and pretension to miracles.

Huc, the Lazarist, seems pleased with this striking similarity, and says, Buddhism has an admixture of truth with holy Church.

Premare, another distinguished Romanist, says, the devil has imitated Mother Church to scandalize her.

Protestants ask, Has not Romanism borrowed from paganism?

(This is the introduction part of Social Life of the Chinese by Justus Doolittle of ABCFM. The book was officially published in 1865.)

No comments:

Post a Comment